So, Are You Good at Forecasting?

Ok then, let’s see. What will be your exact bank balance at the end of the month? Yes, well I’m not so good at that one either.

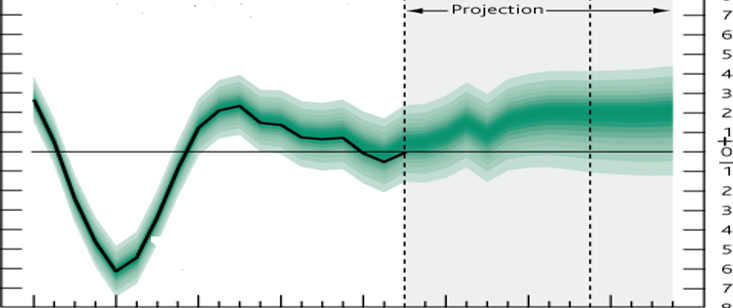

How about predicting what the level of inflation will be at the end of this year? You could have a go, but how certain would you be about that prediction? Would you bet the house?

There are so many factors to take into account; input variables like oil prices, then really complicated things like the impact of substitutions. Unless you’ve got a crystal ball, it’s really hard to see into the future.

Don’t worry, you’re not the only one who might find forecasting difficult. Even big institutions, like the Bank of England and the mighty IMF with all the brains and resources at their disposal, have been criticised for consistently getting their predictions wrong.

So, What’s the Point in Forecasting Then?

Well, as General Eisenhower once said when pressed on his battle plans: “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable!” The same goes for forecasting. It’s a modus operandi.

In fact, I’d go so far as to predict that the skills learned with forecasting could help you with improving your judgement. Let me explain; it’s about phronesis. That word might have you grasping for the online dictionary; it was, in fact, a term bandied about by Aristotle and his philosophy pals, back in the day when Greek civilisation ruled the world of ideas. It’s difficult to translate, not only into English but also into modern day thinking, however, it’s generally accepted as meaning ‘practical wisdom’ or ‘good judgement’. Aristotle was more concerned with practical wisdom as it applied to morality, but good judgement has many applications in life.

Nowadays the goal of attainment of practical wisdom forms the foundation for character education, which a huge number of schools around the world are investing in. One of the issues which Aristotle raised was that ‘the young’ cannot develop phronesis, as they lack the relevant experience.

It’s not clear cut: Igor Grossman, the cognitive scientist, says: “Some people claim that wisdom cannot be trained, whereas others have standing orders on self-help books.” The concepts are abstract and hard to fathom; the answer isn’t always signposted. You don’t just get ‘good judgement’, you have to work hard, adopt good practices over a long period, get the grey hair, so that it becomes habitual to do ‘the right thing’.

What young people need is a framework to help them scaffold their behaviour.

And I think Philip Tetlock, superbrain and author of Superforecasting, might just be able to come to the rescue.

What Exactly is Forecasting?

Forecasting is all about estimating the likelihood of something happening in the future. We’re all forecasters by necessity in life, according to the psychologist Philip Tetlock: “when we think about changing jobs, getting married, buying a home, making an investment, launching a product or retiring, we decide based on how we expect the future will unfold”. These forecasts are then used to make critical decisions.

Philip Tetlock

Why is Accurate Forecasting so Difficult?

Forecasting is easy but forecasting accurately is notoriously difficult to achieve, basically, because no-one knows what the future holds. Chaos Theory proposes that small effects can be compounded into having a disproportionately large impact, described through The Butterfly Effect: how the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil can eventually result in a tornado in Texas. A recent real-life example is how wild animals sold in a wet market in Wuhan allegedly resulted in the Covid pandemic. Who could have predicted that? The knock-on effects of a comestible misdemeanour were huge!

There’s Forecasting Accurately and…..

Then there’s forecasting accurately consistently; enter “Superforecasting”, the art and science of which is the subject of the ex-Wharton Professor Tetlock’s fascinating book.

It began way back in 1987 when Tetlock started to collect thousands of forecasts about the future from hundreds of “experts”, most of whom were just ordinary people from a wide range of backgrounds: retired pipe fitters, civil servants, ballroom dancers, the odd film maker, you name it. The participants had a go at giving their best answer to myriad geopolitical questions like: “Will Russia officially annex additional Ukrainian territory in the next three months?”, “What will be the result of the US presidential election?” Tricky stuff to get right, right? Especially the timing.

Forecasting is not just about predicting whether an event will happen but about estimating the likelihood of it happening; the word ‘likelihood’ throws us into the realm of probabilistic predictions, not just the yes or no digital outcomes. One measure of the accuracy of forecasts is called the Brier Score; this measures the distance between the forecast and what actually happened, taking into account the confidence as well as the outcome. In the world of Brier Scores, counterintuitively, the lower the score the better the prediction is, with perfection (no distance) being 0 and random 50/50 guessing producing a score of 0.5.

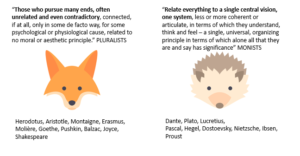

Tetlock categorised forecasters into foxes and hedgehogs, as per the fable of Greek poet Archilochus: “the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”.

In the media, the ‘specialist’ hedgehogs are generally more popular because they use words like ‘certain’ or ‘impossible’, making them seem decisive and expert. Foxes aren’t as well-revered because they quote phrases like ‘on the one hand….on the other hand’ and use probabilities; their arguments might give the impression that they are sitting on the fence and appear opaque. But which are the better forecasters?

Tetlock’s Findings

So, after decades of research, Tetlock concluded that foxes beat hedgehogs hands down in forecasting. Foxes can have real foresight whereas hedgehogs generally don’t. Tetlock also declared that the average pundit or expert is roughly as accurate at prediction as a “dart-throwing chimpanzee”, that is, the same as random guessing. Interestingly, he also found an inverse correlation between fame and accuracy; so, don’t trust the TV star!

The “Art” of Forecasting

Some individuals do consistently outperform, however; that is, they have very low Brier Scores. They are the Superforecasters who over a long period can consistently perform in the top 2%. What characteristics do these people share? Are they superhuman? Superintelligent? Go to the best universities? Well, they are not necessarily who you would imagine. One such Super is Bill Flack, from Cornhusker, Nebraska. He worked in the US Department of Agriculture in Arizona and was by all accounts a good student who managed to get a science degree from University of Nebraska. He’s mid-fifties now and retired. A pretty unassuming guy, right?

What’s he got that the others haven’t?

The Benefit of Teamwork

Tetlock also carried out quite a bit of research with teams to determine the effect.

Teams can be affected by Groupthink, a behavioural bias where members are too polite or too scared to disagree with the leader. Interestingly, Tetlock’s research found that teams were 23% more accurate at predicting than individuals. Teams are successful, or super, if they have strong-minded team members who engage in constructive confrontation, or the team must have members who, in the words of Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel: “disagree without being disagreeable.”

This confirms James Sorowiecki’s findings in his book The Wisdom of Crowds where he concluded that aggregating the judgement of the many consistently beats the accuracy of the average member of the group. This is attributed to the diversity of opinion but only works if the individual members are independent and not swayed by the leaders.

The Good Judgement Project

During his journey, Tetlock went on to found the Good Judgement Project (GJP) in 2011 with fellow academics at the University of Pennsylvania, using 2,800 volunteer forecasters. Through his research, he had identified the best forecasters who were not necessarily subject matter experts but tended to be open minded, data-driven and prioritised probabilities over gut feelings. He put them into teams, teams of foxes, which competed in a government-sponsored tournament launched by the government agency the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency (IARPA), with the objective of trying to determine the best methods of forecasting geopolitical events. Thus, the forecasting skills of the amateurs of GJP were pitted against the top ‘pro’ governmental analysts.

Avoid the Pitfalls of Human Psychology

For human beings, the gut feelings, or so-called behavioural biases, can cause problems. You’re human after all! People have two systems of thinking, described by Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, as the snap, intuitive decision-making, named System 1, and the slower, rational, cognitive approach, described as System 2. The Supers manage the System 1 biases and share a number of common traits and techniques of System 2, which explains their success:

- Process: the mantra “measure, revise, repeat; measure, revise, repeat.” It’s a never-ending process of incremental improvement, referred to as Perpetual Beta. It doesn’t help to make a decision and never change your mind; as John Maynard Keynes declared “when the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, Sir?”

Keynes

- Learn from your mistakes! This is The Growth Mindset. Supers are thoughtful and intuitive updaters

- A strong work ethic and not giving up are essential. You also need to special magic ingredient known as Grit

- Plan: “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable!” as Eisenhower said when he was preparing for battle.

- Reflection is critical: the thinking style should be actively open minded, non-deterministic, intelligent and knowledgeable with the need for cognitive reflection

- Numerate: Supers are generally highly numerate, they understand probability, statistics and confidence levels and can use these tools in mathematical modelling. Big leaps in computing power and continued refinement of forecasting models have nudged the capabilities forward, shifting opinions into the scientific rather than artistic variety

- Dragonfly-eyed: Supers forecast pragmatically, analytically and take in lots of probabilistic perspectives (like a dragonfly’s eye)

- Balance: Harmony is required between under and overreacting, between your own determined internal views and those derived from other outside sources, between under and overconfidence and between prudence and decisiveness

- Focus on future events; Hindsight bias is the cardinal sin in forecasting, it convinces people that prophesies come true! Robert Schiller, the Yale economist, says: “you tend to believe that history played out in a logical sort of sense, that people ought to have foreseen but it’s not like that it’s an illusion of hindsight”

- Fermi-ising: Good forecasters are adept at solving what is referred to as “Fermi-style” problem. Fermi, the Italian physics professor, asked his students big picture questions for which there was no obvious answer, but which could be quantified by estimating the inputs. Trust me, this is the way physicists think. One great example of Fermi-ising cited by Tetlock is that of bachelor Peter Bacchus, a single guy (no doubt Physics student) in London who wants to guestimate the number of potential female partners in his vicinity. He starts his calculations with the population of London, let’s say 6 million, and whittles that down by the proportion of women in the population (about 50%), then by the proportion of singles (c50%), then by the proportion in the right age range (say 20%), by the proportion of university graduates (say 26%), by the proportion he finds attractive (only 5%), by the proportion likely to be compatible with him (10%) and by the proportion likely to find him attractive (only 5%). His mammoth computation determines that there are roughly 26 women in the dating pool. A daunting but not impossible search may begin.

Enrico Fermi

So, these are the skills which drive the Superforecaster’s success. Tetlock concluded that: “Superforecasting demands thinking that is open minded, careful, curious and, above all, self-critical. The kind of thinking producing superior judgement does not come effortlessly. Only the determined can deliver it reasonably consistently which is why our analysis has consistently found commitment to self-improvement to be the strongest predictor of performance.” It demands focus. All of that is what Bill Flack’s got.

How Can all this Improve the Judgement of Youngsters?

The point is: these skills are transferable and are the key ingredients that go in to fermenting good judgement; a critical competency for success in all walks of life. Tetlock believes that people can be trained in forecasting techniques and indeed offers education programmes. However, it must be noted that part of Bill Flack’s superskills is down to his character traits; he has resilience, persistence, dragonfly eyes, the lot!

The earlier you start to build awareness of these attributes the better. Perhaps young people should practise forecasting? Well, that’s exactly what the Alliance for Decision Education in the US thinks. They recently set up a forecasting tournament for students in schools across America to practise decision-making skills. My money’s on more competitions to come.

There are many things young people can do to develop their practical wisdom, such as honing critical thinking, and, by learning about the technical processes, they can improve analytical skills through practice. It is important to understand the circumstances of a situation as much as possible before making a decision and then constantly refine. Allied to self-awareness and character growth, these skills become habituated. It develops into an inherent way of thinking; it’s called good judgement.

The Proof is in the Pudding

So, could Tetlock’s team be confident of making predictions with greater accuracy than chance? Well, after four years, 500 questions and over a million forecasts later, GJP harnessed the skills of the Superforecasters and the wisdom of the crowd to win the IARPA competition in 2015, having “outperformed intelligence and analysts with access to classified data”. Against the odds, they won by a country mile.

Tetlock’s superinspiration was in channelling the publicity around GJP’s success story into offering commercial forecasting and training services to organisations around the globe. Kerching! Only a sly old fox could have predicted that!